Sponsored Search Markets

Search engine queries are a potent way to get users to express their intent — what it is that they’re interested in at the moment they issue their query — and an ad that is based on the query is catching a user at precisely this receptive moment.There can be multiple paid results for a single query term; this simply means that the search engine has sold an ad on the query to multiple advertisers. Among the multiple slots for displaying ads on a single page, the slots higher up on the page are more expensive, since users click on these at a higher rate.

Search industry has developed certain conventions in the way it sells keyword-based ads and it is worth mentioning two of these at the outset.

Pay per click:

If you create an ad that will be shown every time a user enters a query it will contain a link to your company’s Web site — and you only pay when a user actually clicks on the ad. Clicking on an ad represents an even stronger indication of intent than simply issuing a query; it corresponds to a user who issued the query, read your ad, and is now visiting your site.

Setting prices through an auction:

There is still the question of how a search engine should set the prices per click for different queries. One possibility is simply to post prices, the way that products in a store are sold. But with so many possible keywords and combinations of keywords, each appealing to a relatively small number of potential advertisers, it would essentially be hopeless for the search engine to maintain reasonable prices for each query in the face of changing demand from advertisers. Instead, search engines determine prices using an auction procedure, in which they solicit bids from the advertisers. There are multiple slots for displaying ads, and some are more valuable than others.

Auction Mechanism Design

An Illustrative Example:

Consider a specific example of buying a house in a real estate auction. There is one house being auctioned, and eight parties interested in purchasing it. The auctioneer then must determine two things – which bidder wins, and how much they pay for the house. In one notable case of such an auction, the winner was person X (who had the highest bid), and the asking price was his bid. However, being the crafty soul person X is, he made a keen observation. If he, as the highest bidder were simply to refuse to buy the house, the best the auctioneer could expect to receive is the second-highest bid. The auctioneer was therefore being unfair in asking the winner to pay his own bid.

How to design an auction procedure for this setting?

-

If we assume that the advertisers’ valuations are not known, however, then we need to think about ways of encouraging truthful bidding, or to deal with the consequences of untruthful bidding. This leads us directly to an interesting general question that long predates the specific problem of keyword-based advertising: how do you design a price-setting procedure for matching markets in which truthful bidding is a dominant strategy for the buyers?

-

The VCG mechanism provides a natural way to set prices in matching markets, including those arising from keyword-based advertising. For various reasons, however, it is not the procedure that the search industry adopted. We will explore an auction procedure that is used to sell search advertising in practice, the Generalized Second-Price Auction (GSP). GSP has a simple description, the bidding behavior it leads to is very complex, with untruthful bidding. Trying to understand bidder behavior under this auction turns out to be an interesting case study in the intricacies of a complex auction procedure as it is implemented in a real application.

Therefore mechanism design is very important if we want to run a truthful and fair system.

The VCG Principle

What would be a good price-setting procedure when the search engine doesn’t know the advertisers’ valuations? In the early days of the search industry, variants of the first-price auction were used: advertisers were simply asked to report their revenues per click in the form of bids, and then they were assigned slots in decreasing order of these bids. Bidders are simply asked to report their values, they will generally under-report, and this is what happened here. Bids were shaded downward, below their true values; and beyond this, since the auctions were running continuously over time, advertisers constantly adjusted their bids by small increments to experiment with the outcome and to try slightly outbidding competitors. This resulted in a highly turbulent market and a huge resource expenditure on the part of both the advertisers and the search engines, as the constant price experimentation led to prices for all queries being updated essentially all the time.

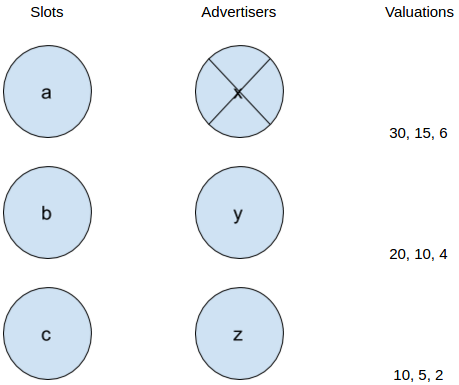

Apply the VCG principle to the market: Under the VCG principle, we first assign items to buyers so as to maximize total valuation. Then, the price buyer j should pay for seller i’s item — in the event he/she receives it — is the harm he/she causes to the remaining buyers through his/her acquisition of this item.

If x weren’t there, y would do better by 20-10=10, and z would do better by 5-2=3, for a total harm of 13.The VCG price an individual buyer pays for an item can be determined by working out how much better off all other buyers would be if this individual buyer were not present.

The Generalized Second Price Auction

After some initial experiments with other formats, the main search engines have adopted a procedure for selling advertising slots called the Generalized Second Price auction (GSP). At some level, GSP — like VCG — is a generalization of the second-price auction for a single item. However, as will see, GSP is a generalization only in a superficial sense, since it doesn’t retain the nice properties of the second-price auction and VCG. In the GSP procedure, each advertiser j announces a bid consisting of a single number bj — the price it is willing to pay per click. As usual, it is up to the advertiser whether or not its bid is equal to its true valuation per click vj . Then, after each advertiser submits a bid, the GSP procedure awards each slot i to the i th highest bidder, at a price per click equal to the (i + 1)st highest bid. In other words, each advertiser who is shown on the results page is paying a price per click equal to the bid of the advertiser just below them. So GSP and VCG can be viewed in parallel terms, in that each asks for announced valuations from the advertisers, and then each uses these announcements to determine an assignment of slots to advertisers, as well as prices to charge. GSP’s rule, when the bids per click are b1, b2, b3, . . . in descending order, is to charge a cumulative price of ribi+1 for slot i. This is because the i th highest bidder will get slot i at a price per click of bi+1; multiplying by the clickthrough rate of ri gives a total price of ribi+1 for all the clicks associated with slot i.

Why use generalized second price auction instead of a first price auction ?

In ad auctions, it is important to remember that auctions take place repeatedly for each keyword and set of ad slots, so each bidder can know approximately the value of a keyword by looking at the results of previous auctions for the same keyword. Therefore, bidders can vary their bid from auction to auction, changing their bid often to reflect changes in the market. This is especially a problem in first-price auctions, where bidders will want to change their bids to be above the second highest bid as slightly as possible. This can cause rapid back-and-forth changes, which puts a lot of strain on the servers of the company running the auction. This is less of a problem in GSP, where bidders don’t have as much incentive to bid below their value, because they will only pay the second highest bid if they win.

Search Engines and the different auction mechanisms they employ:

| Search Engine | Auction Mechanism |

|---|---|

| Slight Variant of Generalized Second Price | |

| VCG | |

| Yandex | VCG |